While some emigrants may face a dilemma regarding their ties with the countries of their origin, as a Chinese living in Singapore, I have never felt disconnected with the motherland. This is partly because advancing internet technology provides me with timely news feed, and I remain an active user of Weibo, so that Socialism with Chinese Characteristics still influences me and maintains my sense of existence. At the same time, because I moved to Singapore when I was 16, my social identity lacks some of the conformity shared by my peers back home. After being away for so long, my family and not much else seems to keep me connected. Travelling home, therefore, becomes a journey of exploration to some extent.

Having lived with the pandemic for two years, I have become used to Singapore’s way of controlling the outbreak, such as the circuit breaker (a partial lockdown), no dine-in (unvaccinated individuals are prohibited from dining in at restaurants) and the 5-person-dine-in rule (maximum group size for social gatherings limited to five individuals) that were implemented at various points in time in the last two years. I still experienced my first culture shock when I faced China’s strict pandemic measures. The 21-day quarantine to be spent at a designated hotel is a well-known rite of entry into Shenzhen, but I was still impressed by the city’s pursuit of efficiency. By then, the situation in Shenzhen had moved back to normal for a while and the city was yet to suffer from the most recent omicron wave, but most people did not appear to subscribe to the “living with the virus” theory. Many were proud of the efficiency that Shenzhen government has demonstrated when dealing with emerging cases.

The numerous delivery riders across Shenzhen play a crucial role in the city’s digital economy.

Source: author

The numerous delivery riders across Shenzhen play a crucial role in the city’s digital economy.

Source: author

As I did not get many opportunities to engage with others in person during my quarantine, I spent much time exploring the famous mobile apps. My quarantine hotel did not allow food delivery, but fortunately I was able to order fruits, milk and well-packed snacks. The average waiting time was 20 minutes, and interestingly, one would be compensated by an insurance if your order was delayed by 10 minutes or more. This service offered a large variety of goods, ranging from groceries to cosmetic products; I ordered a box of contact lenses after I accidently broke my glasses. It really felt like the entire supermarket had moved online as even fresh products like vegetables, meat and seafood were available. With this in context, the rapid expansion in China of Community Group Purchase—through which buyers form a community and place orders in bulk at better prices—becomes easy to understand. Indeed, there are many mobile apps in service. The famous tier-1 apps include food delivery giant Meituan, Pingduoduo (which connects millions of agricultural producers with consumers) and online retailer JD.com; lesser-known up-and-coming services include online retail service providers Dingdong, Hema, Yonghui, DMall and Meicai.

Their expansion has shaped people’s lifestyle—or to put it differently, they appear to have successfully educated consumers and created demand. Back in 2008, if Alibaba-owned online retail platforms Taobao and Tmall addressed people’s needs to get practically anything (physical or virtual) in days, now Meituan has managed to satisfy consumer demand in hours and minutes. This is the result of affordable labour, cutting edge operation research algorithms, innovative monetisation strategy and supportive capital markets. I don’t think the service can be easily replicated in other markets in Asia, at least not with enough profit margin to survive the initial customer acquisition phase.

On ride hailing, Didi appeared to be on the wane with Alibaba-owned AMap now the new go-to app. User acquisition has never seemed so easy for an internet company such as AMap; it can create a sticky user base as the core business is navigation, and it can also benefit from massive traffic directed from online and mobile payment platform Alipay. Because the payment infrastructure is already in place, AMap ride hailing for users is truly a “plug and play” experience. The user does not even have to install the app, as the service can be accessed via mini-apps (smaller apps with limited features that exist in larger apps). Separately, I believe this is also why Meituan is spending a lot of money building its own wallet. Payment does not make money, but it facilitates business model innovation and monetisation.

Speaking of payment services, the rivalry between Alipay and WeChat Pay remains ongoing. On Shenzhen’s streets, the green coloured QR codes were accepted everywhere. More formal and standardized shops accepted both wallets, and interesting to find out that some point-of-sale (POS) terminals are made by Meituan. They penetrated every corner of the value chain. Cash has seemingly disappeared—I never had to use cash during my stay in Shenzhen. WeChat Pay dominated small size payments for shopping mall purchases, entertainment and taxis. Credit card penetration is not comparable to that of developed countries, largely because Alipay Huabei (and other similar services), which allows users without credit cards to pay for their purchases in instalments, are the default payment method, followed by E-wallet balances, credit cards and bank balances. Many of my friends do not have a credit card, and they probably will not get one anytime soon.

Some other observations during my stay were:

- Most taxis in Shenzhen had green plates (issued to EVs) and were predominantly supplied by the automaker BYD. This is another example of Shenzhen being a pilot of emerging technologies and business models. Taxi drivers noted that EVs are cheaper in the city but required a longer battery life. While the vehicles are designed to run 400 kilometres per charge, they need to be recharged every 300-350 kilometres in reality. Charging stations are widely available across the city, and cutting-edge fast charging technologies can replenish 80% of the battery in half an hour.

Most taxis in Shenzhen were EVs predominantly supplied by automaker BYD. The city’s buses were also mostly EVs.

Most taxis in Shenzhen were EVs predominantly supplied by automaker BYD. The city’s buses were also mostly EVs.

Source: author - Some restaurants are seemingly going through an industrial revolution. They use pre-packed ingredients, which are mixed up and heated in ovens and served to customers. Overall, it is a business model with lower margins, lower labour costs and higher turnover. A good example would be bubble tea (tea-based beverage commonly served with tapioca and other toppings) chain MXBC. While MXBC is perceived as a beverage franchise, it could be considered a supplier of raw materials in reality.

-

Those of my generation (and probably those of the younger generation as well) have an astonishing willingness to pay for E-gaming. I started playing the famous MOBA (multiplayer online battle arena) game Honour of Kings in 2021, and I have spent roughly Singapore dollar (SGD) 1,000 on the game. However, I was shocked when I found out that my younger brothers and nephews have easily spent SGD 1,000 per year on E-gaming for features such as virtual outfits and lucky draws. Digital payment methods are well-integrated within the game and have largely facilitated the transactions. Monetisation is designed around encouraging virtual outfit collections, limited offerings, honour rankings, opportunities to show off your achievements to your peers and lucky draws. For example, Genshin Impact, an open world-exploring Japanese fantasy game developed by a Shanghai-based company called Mihoyo , has done remarkably well.

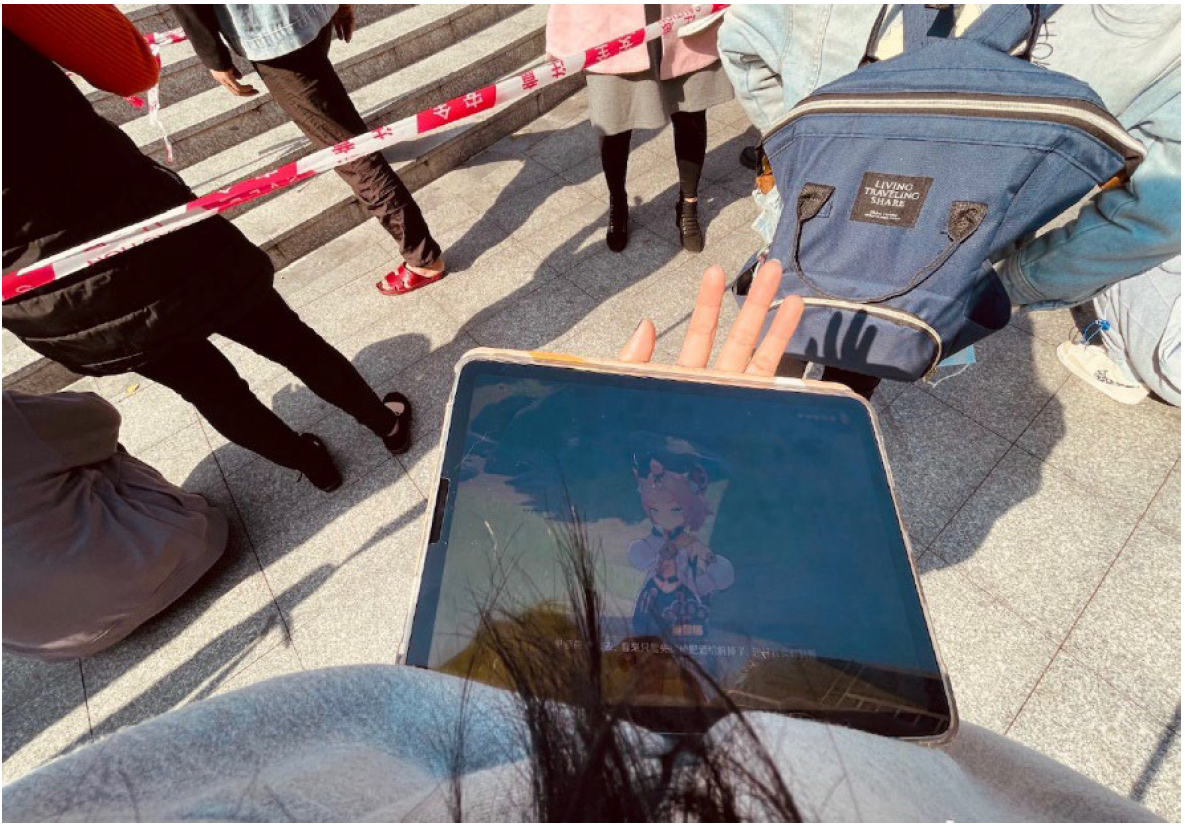

A Shenzhen resident plays Genshin Impact while waiting to take a PCR test.

A Shenzhen resident plays Genshin Impact while waiting to take a PCR test.

Source: author - Tiktok (also known in China as Douyin) and other video-sharing apps like Kuaishou are known to be highly addictive and have penetrated wide swathes of the population. It still surprises me when my 78-year-old grandmother, who is not literate, asks for a smartphone so she can swipe Douyin videos. Gross merchandising value (GMV) transactions on short video platforms are mind blowing, and the rise of key opinion leader (KOL) marketing—in which brands work with people who are considered experts on certain subjects—appears to be stimulating people’s consumption urges.

Overall, my short stay in Shenzhen was an eye-opener. I was surprised by its stringent but efficient measures against the virus, by its fast roll out of EVs as an infrastructure, and particularly by its digital penetration. Shenzhen’s younger generation are internet natives and their consumption behaviours are shaping the digital economy and defining the next business model. Many innovative monetisation strategies are incubated in Shenzhen and have gone nationwide and even worldwide. As an investor, I would keep a close eye on Shenzhen for a clue to where China is heading in the areas of 5G, EV, autonomous driving, the metaverse and many other emerging areas.

Reference to individual stocks is purely for illustrative purpose and does not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any securities or to be relied upon as financial advice in any way.