Key Takeaways

- A changing geopolitical landscape in Asia coupled with a desire to partially diversify away from China-based supply chains is creating opportunities in India and Indonesia.

- Decoupling will not be easy given China itself is a huge market and leads in many industries, especially technology and materials needed for tackling climate change.

- Even so, a broader Asian focus could be wise for investors. India and Indonesia—which both have large, young and lower-cost workforces and are benefitting from a series of favourable government initiatives—are worthy of further consideration.

After a challenging year in economic growth terms, compared to initially heightened expectations, a “de-risking” of supply chains away from China is increasingly evident, with investment capital being reallocated into India and ASEAN countries such as Indonesia. The year began with high hopes of an economic resurgence for China following the lifting of strict pandemic restrictions at the end of 2022. However, business activity has been disappointing, amid poor earnings reports from listed companies, and continued concerns about China’s ailing property sector.

Geopolitical risks remain

This economic weakness is taking place at a time of ongoing geopolitical tensions between the US and China, and the fractious relationship between the world’s two largest economies has become a global concern. When ex-US president Donald Trump started his trade war against China, many production-focused companies accelerated their moves away from China (which were already happening, thanks to higher Chinese wages) to other parts of the world including Asia. This process is continuing. In May this year, the G7 group of countries spoke of “de-risking” their economic ties with China, rather than the more diplomatically emotive “decoupling”. Most recently, in August, US President Joe Biden signed an Executive Order imposing new restrictions on US investment in high-tech Chinese companies, and placing further economic barriers between the two countries. The barriers to investment in China have led to Western money either staying local or flowing to other nations that can offer a cost-effective and credible alternative.

Placing China’s difficulties in context

China’s population has peaked—and will be overtaken by India this year1—and it has continued to face economic challenges since COVID. However, it would be unwise to bet on the longer-term demise of China, or its status as the world’s second-largest economy. Some of these geopolitical changes are creating opportunities in China too with local brands being preferred by consumers, localisation efforts driving investment and self-sufficiency in areas of industrials, technology and energy. For the rest of the world, China remains a key trading partner and is a global leader in efforts to tackle climate change and other challenges.

For example, with the largest scale of solar panel production, China dominates the solar energy supply chain. It is also now the world’s major producer and consumer of electric vehicles (EVs). As a result, China will continue to play a central role in the global energy transition. It also remains at the forefront of technological development in artificial intelligence, machine learning, robotics and space. Indeed, the recent executive orders from the US appear designed to counteract the threat of China becoming unstoppable in the tech innovation “arms race”.

Moreover, the Chinese state does appear to recognise that it needs to change and reform, and Beijing is able to execute such changes very quickly. During the summer, the Chinese government announced a raft of measures aimed at attracting more private capital, boosting electric vehicle ownership and the purchase of consumer goods, as well as efforts to shore up the real estate market. Looking more long-term, retirement age reforms, social safety nets and household registrations are all areas where China can implement swift changes. The third Plenum, a meeting of the National People's Congress (NPC), later this year is likely to be very important. Given China’s leaders seem focused on addressing deeper issues within the economy, the prospect of a large package of reforms is much greater than would have been possible a year or so ago.

India and Indonesia: both benefitting from the demographic dividend

But as all investors should know, diversification is a valuable tool. The question for global investors to ask then is which countries stand to benefit the most from production moving away from China? At present, two of the biggest beneficiaries are India and Indonesia. Both countries are still on relatively friendly terms with China and the US, and they have their own large domestic markets to cater to. They also have the advantage of very large, young workforces, meaning both countries can entice overseas producers with the promise of cheaper labour.

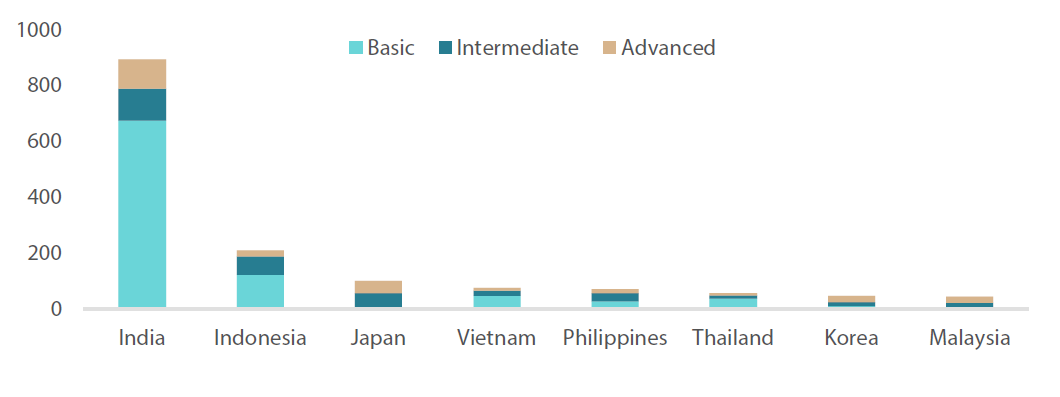

India and Indonesia have achieved rapid economic growth over the past few decades, and one of the primary drivers behind this growth is their demographic dividend. Chart 1 shows India and Indonesia’s working-age populations compared with other Asian countries. A younger workforce is generally more adaptable, willing to learn and can be trained in new skills and technologies. This adaptability can drive innovation and help in the adoption of newer technologies, thereby fostering economic progress. Also, both India and Indonesia have attracted significant foreign direct investment (FDI) in industries like manufacturing, IT services, textiles and more, thanks to their competitive labour costs.

Chart 1: Working age population by education (millions)

Source: International Labour Organisation, Nikko AM

Source: International Labour Organisation, Nikko AM

Government initiatives are bearing fruit

India and Indonesia are also reaping the benefits from strong government initiatives and reforms.

India, for example, has introduced initiatives such as the Goods and Services Tax (GST) and the Real Estate Regulatory Authority (RERA) Act, which was brought in to protect the interests of real estate buyers and developers alike.

Arguably the most encouraging and forward-looking initiative is a review of the 2020 Production Linked Incentive Scheme (PLI), which is available in 14 manufacturing sectors including: mobiles, medical devices, telecom and networking products, automobiles and auto components, pharmaceuticals, drugs, white goods, speciality steel, electronic products, food products, textile products, solar PV modules, advanced chemistry cell batteries, and drones and drone components. Thanks to the PLI, India’s tax rate for new manufacturing is now among the lowest of its peers.

By contrast, Indonesia has gone a different route. In 2020 it passed its Omnibus Law, officially known as the “Job Creation Law”. This legislation was intended to streamline and simplify Indonesia’s then-complex web of overlapping regulations to bolster economic growth and investment—particularly FDI which can help bolster a country's reserves and support its currency.

This policy has been necessary ever since the Asian Financial Crisis of the late 1990s, when, along with many Asian currencies, the Indonesian rupiah suffered a massive devaluation. Since then, Indonesia has been focused on stabilising its currency because its external account (which encompasses its trade balance, net income, and net transfers) has been weak.

The combination of capital inflows for FDI, as well as more confidence in Indonesia's policy-making capabilities from investors, means its currency is more stable and policy can now be run based on what the domestic economy needs. This is, of course, a significant positive shift for the country, both domestically and internationally.

Indonesia is becoming more than just a raw commodities exporter

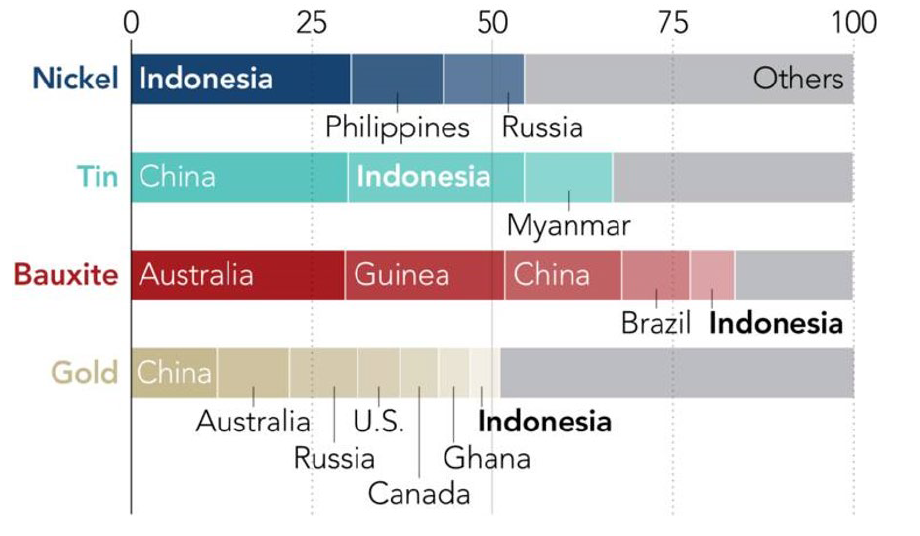

One example of where Indonesia’s domestic focus is reaping greater rewards comes with its push to move up the value chain in the nickel and copper sectors. Historically, Indonesia has been a major exporter of various commodities ranging across the commodity spectrum from oil, coal and gas, palm oil and various metals like nickel, bauxite and copper. In fact, Indonesia has the largest nickel reserves in the world. That said, being an exporter of primary commodities means Indonesia has historically been at the mercy of global trade flows, while other countries have reaped the benefits of converting those commodities into finished goods.

By banning nickel exports, President Jokowi's administration aims to transform Indonesia from a primary exporter of raw materials into a producer of higher-value, processed goods, ultimately benefiting the nation's economy and its standing in the global market. Moreover, as nickel is a key component in the lithium-ion batteries used in EVs, focusing on the domestic processing of nickel could see Indonesia position itself as a major player in the EV battery supply chain, potentially even producing the batteries themselves, which are significantly higher in value than raw nickel.

Chart 2: Indonesia has some of the world’s most valuable mineral reserves

Source: U.S. Geological Survey

Source: U.S. Geological Survey

Diversified Asian exposure

For many investors, an allocation to Asia (ex-Japan) is always likely to be dominated by a heavy weighting towards China. But we would suggest that now is a good time to think about a broader Asia (and indeed ASEAN) focus that includes countries such as India and Indonesia, both of which have their own distinct advantages, and are taking bold steps to grow their own respective economies.

To learn more about diverse opportunities in Asia, download Nikko AM’s investment guide: Harnessing Change in Asia here.

For any questions in regards to this report, please contact:

Nikko AM team in Europe

Email: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.