External uncertainty is driving financial market volatility

The financial markets, buffeted daily by the steady streams of news and noise on US trade policy, have experienced wide swings in sentiment. Expectations have fluctuated between hopes for the best and fears of the worst. An optimistic outcome, in our view , would most likely be characterised by trade détente and reversals of many of the largest threatened and imposed tariffs of early April. The worst-case scenario is based on fears of a US recession and its impact on other economies, which are possibilities we have also explored in our scenario framework 1 .

Japanese equities have not been immune to tariff worries, particularly regarding product-specific tariffs on items like automobiles and steel. These worries have been reinforced by significant downward revisions to earnings in the wake of the initial tariff announcements. Sporadic strengthening of the Japanese yen spurred by risk aversion in response to negative developments has also dampened sentiment towards large-cap exporters. However, those focusing on Japan's large-cap exporters as a barometer of economic health may be missing out on the important long-term message - that Japan is undergoing structural reflation driven by factors unlikely to be reversed by market volatility or bad news on US trade.

Investment is bigger than trade

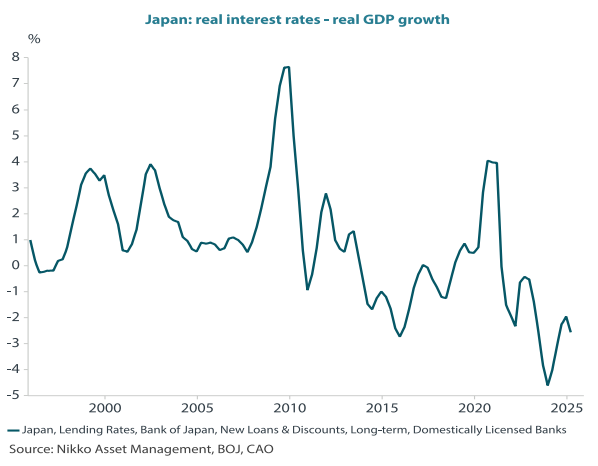

Japan maintains considerable bilateral trade surpluses with the US. However, we highlighted in How Japan can safeguard against US tariffs (16 January 2025) that the greater contributor to Japan's robust current account surpluses is not trade but overseas investment - or reinvestment of the returns realised on its direct and portfolio investments in other economies. These surpluses (see Chart 1) accumulated by corporations and institutional investors could decrease over time, but if they did, it would likely indicate a narrowing growth differential between investment destinations and Japan. In essence, the returns on these investments represent capital that may be easily repatriated should overseas investments cease to yield returns.

Chart 1: Investment Income dominates Japan's current account surplus

Source: Nikko Asset Management, BOJ

For the moment, despite the uncertainty surrounding US trade, there are few signs of significant deterioration in the performance of Japan's overseas investments. Moreover, there are signals of continued resilience in Japan's economy, even in the face of external uncertainties. These factors may encourage rational investors and trade partners to remain invested in Japan's steady exit from its deflationary lost decades.

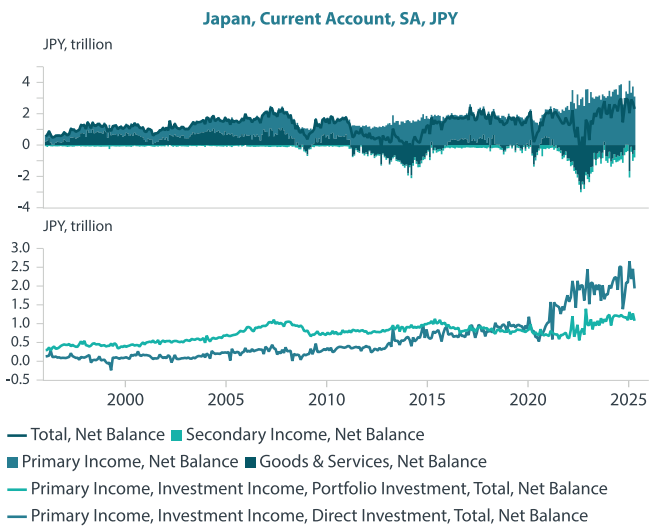

More than trade, inflation is a challenge for (real) growth

Japanese GDP growth recently posted a negative reading, driven in part by softness in net exports in the quarter prior to Washington's announcement of the “reciprocal” tariffs. Nonetheless, the greatest factor affecting real growth was not exports. As shown in Chart 2, nominal GDP growth remains positive year-on-year, while real growth is negative. We observe that the nominal expansion in household consumption significantly outweighed the drop in net exports. Nonetheless, the picture is starkly different in real terms. Household consumption was not hindered by trade-related uncertainty, but by inflation, as evidenced by the consumption deflator nearing 3%, which is a decidedly non-deflationary trend. Japan is facing a very different problem compared to its “lost decades” of deflationary growth, when it relied on price declines amid negative nominal growth to deflate its way to real growth.

Chart 2: Inflation, not exports, weighs on real Japan GDP growth

Source: Nikko Asset Management, CAO

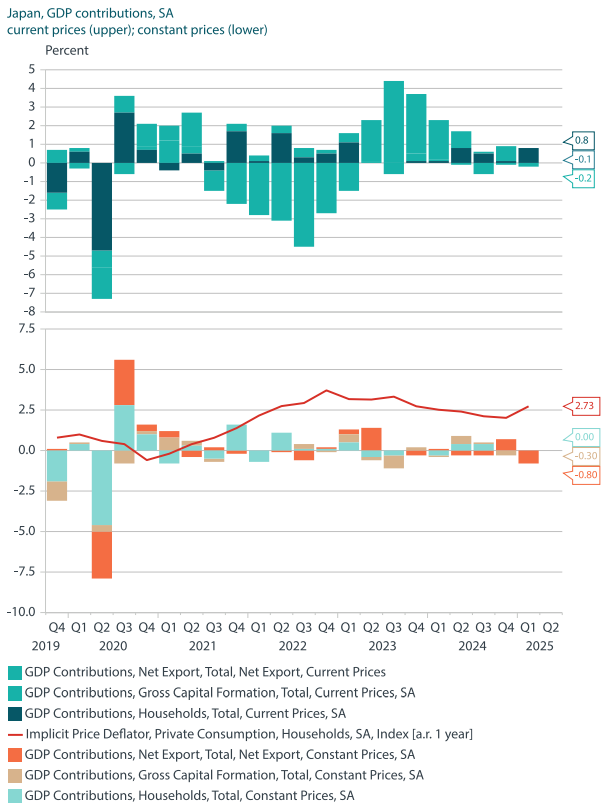

After lost decades, corporate Japan goes from zero to reflationary hero

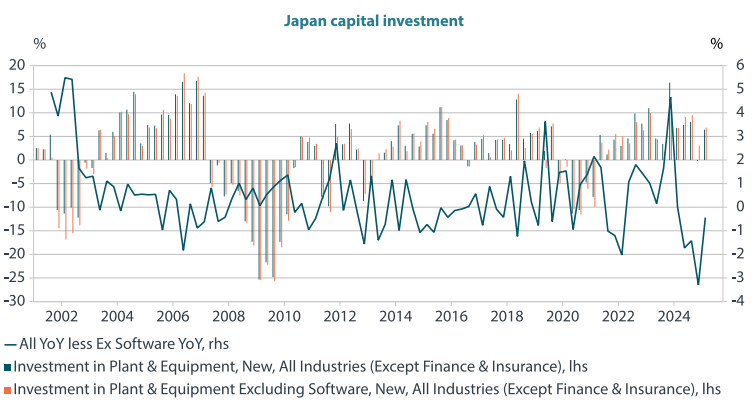

An emerging trend is the extent of structural change affecting Japan's corporates, which goes much further than coasting on a weak yen and healthy export and investment revenues from abroad. As reflation takes hold in Japan, we may witness the benefits corporates have accrued. Revenues in nominal terms have contributed to strong profit growth among companies (see Chart 3), who have been able to improve their margins as they regained pricing power. Meanwhile, one legacy of deflation—years of hoarded cash on corporate balance sheets—appears to be reversing (see Chart 4) as companies pay higher wages to attract and retain labour and make overdue investments to upgrade their tangible and intangible assets (see Chart 5). While there was a brief dip in capex growth at the end of 2024 after several quarters of strong private sector expenditure, corporate investment (including investment in software) posted a healthy rebound in early 2025.

Chart 3: Corporate revenues have benefited from nominal GDP growth |

Chart 4: Corporate cash-hoarding may be peaking |

|

|

Chart 5: Japan witnessing a resurgence in capital expenditure

Source: Nikko Asset Management, MOF

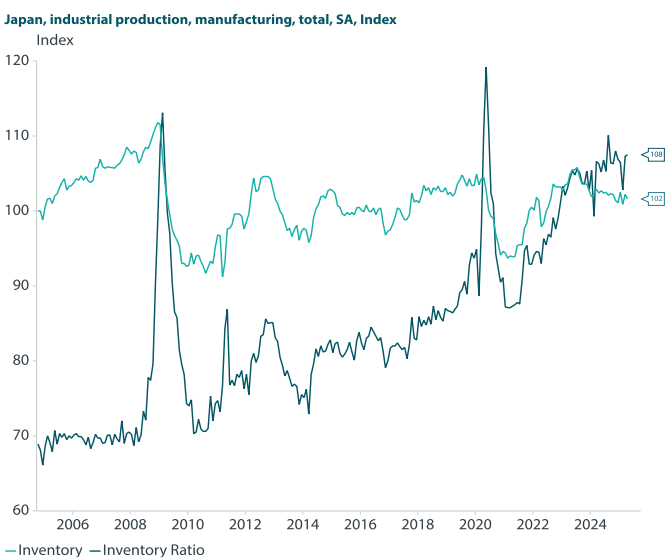

Despite the undeniable uncertainty stemming from the US tariffs announced since 2 April, corporates - long accustomed to stop-start growth cycles - appear to be managing their inventories prudently. Chart 6 shows why any delays in orders related to the April tariffs uncertainty may have had little impact on industrial capacity. This is because companies had already been reducing inventory levels in the preceding quarters, maintaining steady inventories-to-shipments ratios. Earnings guidance may have been managed even more conservatively than inventories in sectors directly impacted by tariffs; revisions often appeared to reflect worst-case scenarios. By the same token, if the negative impact of the tariffs on export-sector profitability is smaller than expected, valuations could be lifted from near-20-year lows later in the year.

Chart 6: Inventories are being managed prudently

Source: Nikko Asset Management, METI

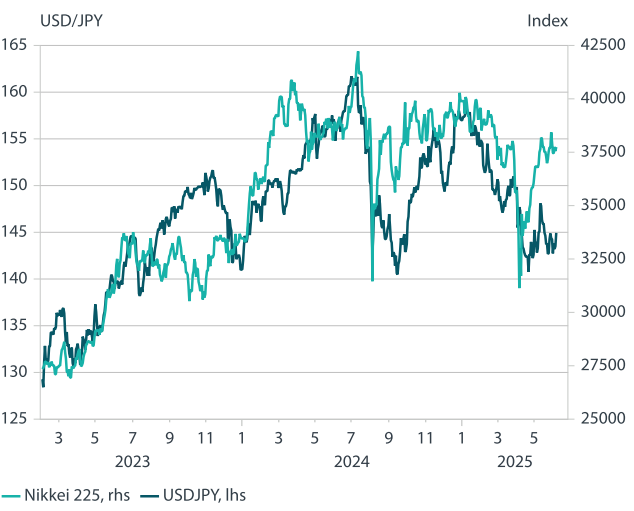

The cautious inventory management approach taken by the companies as described above could be one reason why the large-cap exporter and tech-heavy Nikkei 225 is no longer trading in lockstep with dollar-yen (see Chart 7). Sceptics, of course, may see clause 899 of the pending US Budget Act, which threatens to impose retaliatory taxes on investments of subjectively “unfair” tax regimes, as a potential source of concern for big investors in the US. Japan, via its large corporations, is the largest national foreign direct investor in the US. These large Japanese corporations may not view tariff threats and related uncertainty merely as the “cost of doing business” with the US.

Chart 7 : Even large-cap exporter, tech-heavy Nikkei is decoupling from dollar-yen

Source: Nikko Asset Management, Macrobond, Nikkei inc.

One often-overlooked aspect of this is the benefit of earning revenues overseas. Japan's position as a major creditor to the US gives it the option to vote with its feet if it needs to. Japan could opt to liquidate US investments that are no longer viable due to the rising cost of doing business. Japan has already started to tap Japanese yen (JPY) 388 billion from domestic government reserves to offer relief to corporations hit hard by US tariffs. It is plausible to consider that the solution to diminishing investment returns abroad is repatriation rather than capitulating to constantly shifting US demands.

The household quandary: keep inflation from stifling growth

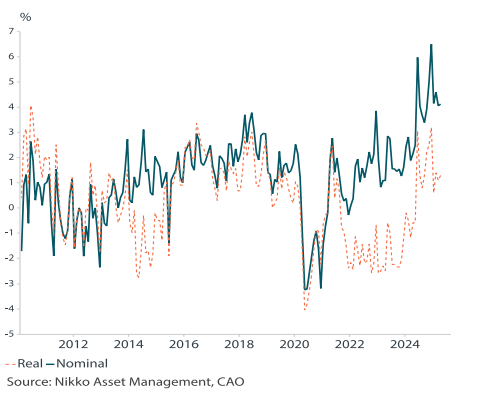

Although headline and core inflation have now remained above the Bank of Japan (BOJ)'s 2% target for about three years, the central bank has not declared a definitive victory over deflation. This is mostly due to the lag in household demand compared to the relative health of Japan's companies. However, greater nominal profits, rising costs and labour supply shortages have eventually pushed companies to raise wages (with a lag to profits), and to invest in future productivity. As shown in Chart 8, nominal wages have increased for several years.

Chart 8: Nominal vs real labour cash earnings growth

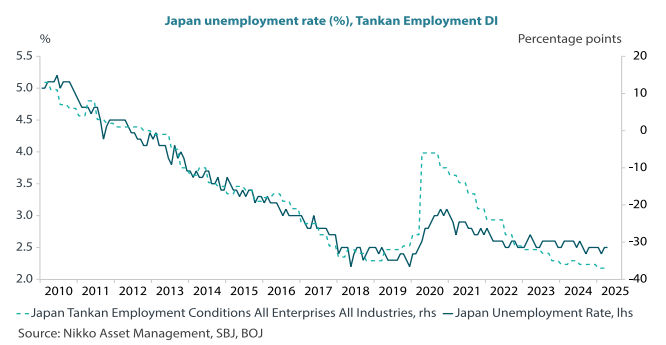

For households, real balances matter. Thanks to persistent inflation, real wages have only recently turned positive, with record wage agreements by unionized labour at the annual Shunto spring wage negotiations finally filtering through into the broader economy. Currently, inflation is the main challenge to households' otherwise expanding purchasing power, marking a significant departure from Japan's “lost decades”. Moreover, this new dynamic has roots in a structural component of Japan's labour market, characterised by chronic labour supply shortages (Chart 9), which are particularly acute in labour-intensive services industries.

Chart 9: Structural labour shortages go beyond simply low unemployment

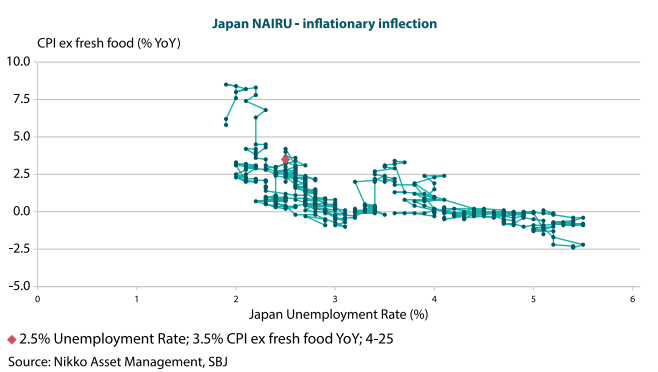

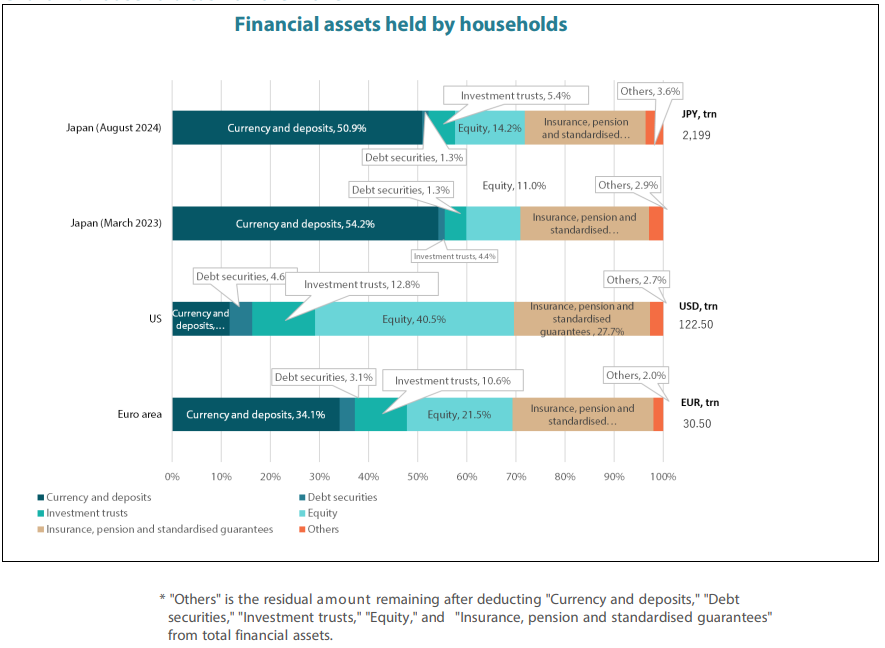

We may observe that the unemployment rate, which is currently in the low 2% range, is lower by some measures than “full” (non-inflationary) employment (see Chart 10) and is historically consistent with accelerating inflation. Although the total balances of household cash have not yet shown signs of depletion (see Chart 4) despite the move towards higher prices and wages, Chart 11 shows us that reallocation already took place between fiscal 2023 and 2024. The introduction of the new NISA, which offers tax incentives, has had some success in moving savings to investments. The proportion of household assets held in cash decreased significantly between fiscal 2023 and 2024, from over 54% of households' balance sheets to slightly over 50%, with investment trusts and equities the main beneficiaries.

Chart 10: Low unemployment is consistent with price rises

Chart 11: Household cash on the move

Source: Bank of Japan, sjhiq.pdf (boj.or.jp)

Reflation, savings-to-investment keep domestic buffer intact

Japan has seen positive developments in wage growth, an increase in nominal consumption and shifts in household assets from cash to financial market instruments. Given these favourable trends, there is reason to believe that households will continue to provide the growth buffer that Japan needs at a time of external uncertainty, as long as inflation remains contained relative to income levels. Labour supply shortages are likely to continue compelling corporations to reallocate their cash reserves (currently slightly below JPY 350 trillion in total) to compete for scarce labour, replenish depreciated assets and invest in future productivity. Meanwhile, although households tend to respond to inflation with a lag, the shift from deflation-era cash hoarding towards investing in the market has begun. This shift means that a portion of the JPY1.1 quadrillion currently held in cash will need to be deployed to positive-yielding assets to protect households' future purchasing power from stubborn inflation.

Ultimately, if the quantity of money is indeed an inflation driver, as Milton Friedman suggested in 1963, it is the BOJ's role to respond to the principal threat to households' purchasing power. As we noted above, the BOJ is yet to acknowledge the restoration of the traditional relationship between supply and demand of money. Meanwhile, external demand uncertainty has cast a pall over the BOJ's policy normalisation trajectory. Barring an unforeseen collapse in domestic demand, the BOJ could still resume removing accommodation before the end of 2025, should inflation continue to pose a credible risk to real growth.

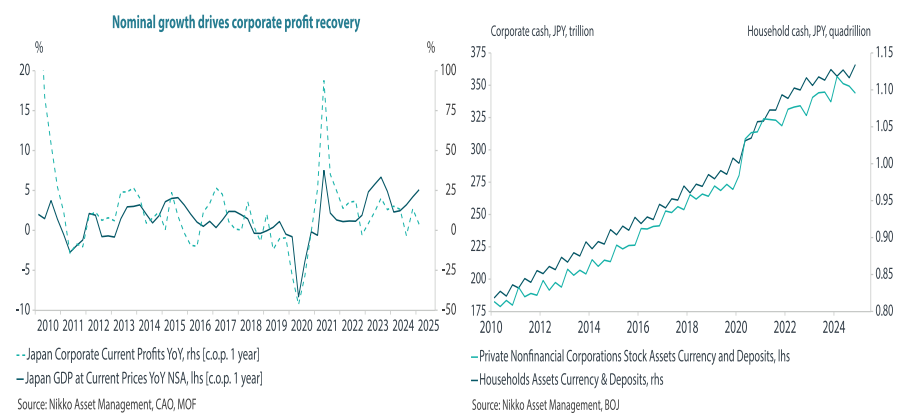

To gauge the current state of accommodation, we refer to Chart 12 (real interest rates minus real growth), which shows us that the BOJ still has room to remove accommodation without interest rates becoming restrictive. Ongoing evidence of household resilience amid external uncertainty may give the BOJ greater confidence in pursuing rate normalisation to keep domestic growth alive and well.

Chart 12: Interest rates are still accommodative